Housing access in Massachusetts is at a crisis level. A two-bedroom apartment in MA, the third most expensive state for housing, requires an annual household income of over $86,000. These costs are exacerbated by low housing inventory, especially among affordable units. The deficit of affordable and available housing for extremely low-income residents has grown to over 175,000 units. Meanwhile, builders are financially incentivized to develop luxury housing rather than desperately needed affordable units. The result is a housing “cost burdened” scenario. This painful dynamic occurs when residents spend 30% or more of their gross income simply to acquire and maintain housing.

Organizations such as the Citizen’s Housing and Planning Association (CHAPA) are working to improve the availability and affordability of housing in Massachusetts. In the spring of 2023, we asked Dana LeWinter, the former Director of Municipal Engagement at CHAPA, about the organization’s approach to this important work.

Affiliated with CHAPA for nearly 20 years, Dana’s aim has been to move housing policy forward. After working as a CHAPA intern in 2004, she returned in 2009 to manage the Massachusetts Homeownership Collaborative for two years. In 2018, she came back to CHAPA to transform local housing policy through an exciting initiative described later in this post. Dana is now the Chief of Public and Community Engagement at Massachusetts Housing Partnership.

The Start of the Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association (CHAPA)

In 1967, a small group of community leaders established CHAPA. Their mission remains the same as it was then—to encourage the production and preservation of affordable housing. CHAPA’s work is guided by the belief that everyone should have safe, healthy, and affordable housing. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines affordable housing as when “the occupant is paying no more than 30 percent of gross income for housing costs, including utilities.”

And, according to Dana, affordable housing solutions must fit residents’ needs and budget. Healthy housing looks different depending on people’s varying needs. This includes the standard definition of healthy housing—dry, clean, safe, etcetera—as well as appropriateness for family size, mobility needs, and access to essentials like grocery stores, pharmacies, and public transit.

Addressing the Root Causes of Housing Inaccessibility

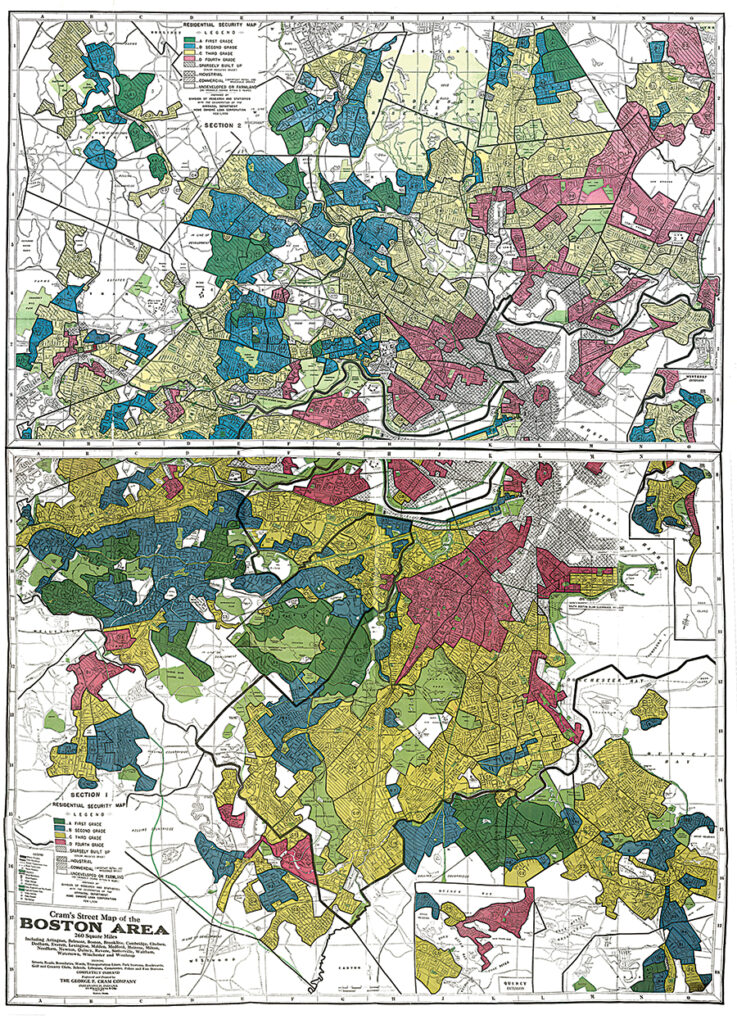

One of CHAPA’s approaches to increase affordable housing in the Commonwealth is to reduce racial patterns of segregation in Massachusetts communities. The Greater Boston area and Massachusetts are highly segregated, much of which can be attributed to the historical practice known as redlining seen in Figure 2.

REDLINING: A discriminatory practice that consists of the systematic denial of services such as mortgages, insurance loans, and other financial services to residents of certain areas, based on their race or ethnicity.

Redlining disregards individual’s qualifications and creditworthiness to refuse such services, solely based on the residency of those individuals in minority neighborhoods; which were also quite often deemed ‘hazardous’ or ‘dangerous.’

(Legal Information Institute)

This harmful practice has left many Black families unable to build generational wealth the same way that white families have, producing and perpetuating a racial homeownership gap.

In addition to redlining, exclusionary zoning practices have also contributed to the Massachusetts housing crisis by preventing new homes from being built and limiting the types of housing that can be built in certain communities. To expand those who can access affordable housing, CHAPA is currently supporting the MBTA Communities Law, which aims to create more housing opportunities for people who have historically been excluded. The 175 communities with MBTA stations outside of Metro Boston must zone at least one district “of reasonable size” for multi-family housing near stations. This zoning mandate will not require building new homes but rather change how local housing decisions are being made and make it easier for more housing to be built. For example, the zoning mandate moves municipal zoning decision-making from groups of people who often don’t represent the broader needs of their community to the residents who will be most impacted by these decisions. .

Dana sees CHAPA’s constellation of approaches as crucial to advancing housing equity. “[T]here’s a tendency, I think, for folks to want to see one thing as the solution,” Dana explained. “Is it rental assistance? Is it zoning changes? Is it state funding or one of these things? But it really does have to be this holistic approach, and that’s the attitude that we try to take at CHAPA, to put all those tools towards our efforts.”

Changing Local Housing Policies through the Municipal Engagement Initiative

Housing infrastructure and policy across the Commonwealth is highly variable. “We have 351 cities and towns here in Massachusetts that all have their own form of government. They have their own zoning and planning boards,” Dana shared. “And if we can’t move forward actions at that local level, we’re never going to meet our real housing needs as a state.” Advocacy efforts throughout the state can benefit from sharing their resources and best practices for driving housing policy change in their communities. CHAPA’s Municipal Engagement Initiative (MEI) serves as a resource for residents throughout Massachusetts. MEI informs Massachusetts residents about housing policy and increases learning across coalitions.

Created six years ago to target local housing policy, MEI is one of CHAPA’s largest programs. The impact of their work can already be seen at the local level. To date, MEI participant communities have (1) passed inclusionary zoning, which requires affordable units to be set aside when new market-rate development is built, (2) created Housing Trust funds, (3) passed housing production plans, and (4) advocated for their town-owned land to be set aside for affordable housing. Not only have these wins happened in individual towns, but Dana believes that MEI has created broader impact by emphasizing the importance of having adequate, diverse housing opportunities in every community.

MEI is funded in part by the Massachusetts Community Health and Healthy Aging (MACHHA) Funds, a collaborative project of the MA Department of Public Health (DPH) and Health Resources in Action (HRiA). Figure 3 shows Dana and colleague Lily Linke in 2022 at the MACHHA Funds showcase event holding their poster illustrating MEI’s impact.

CHAPA: Fostering Diverse, Sustainable Communities Through Planning and Community Development

MEI is just one of CHAPA’s many programs, all designed to improve housing access. Collectively through their portfolio of programs, they aim to create 200,000 new homes by 2030. Achieving this goal drives progress toward more equitable housing and social outcomes throughout Massachusetts.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Reena Dixit, former BU Activist Fellow, for her role in concept development and interview facilitation, as well as Christine Gordon-Davis and Erna Alfred Liousas for their editing support.